Here you'll find all my archives works which will include essays, data analysis, critique, nad reports on a variety of subject matters and in a variety of disciplines relevant to my interests and expertise. Many of these will come from my old University work. All should be referenced, some using different references styles. Each should have an overview at the top describing the item. If there are any discrepancies you deem critical to any of these that disenfranchise references individuals, or you consider harmful you can email me directly with the contact details on the home page. Everything here will be dated, and concluded, meaning I have no intention of going back to edit, or continue any of these works unless it is critical to do so for integrity purposes.

Forensics and Science

Unfortunately, in this section of Forensics and Science due to some of the content in a handful of my reports, expert witness statements, among other works, I have opted to exclude them. As much as I'd love to put all my work here, some of them contain graphic content, information, and breakdowns I personally would be uncomfortable and concerned with putting here. Rest assured all content present, is safe for work.

This report was written for the University of Otago in the paper CHEM306 over a two week long lab cycle.

Quality assurance in any scientific forum is important to ensure an analysis is reliable, reproducible, and meaningful. But the quality assurance of any workload is never without some amount of uncertainty, and so in order to maintain transparency and reliability, we not only analyze the results, but we analyze the methodology, equipment, and technique that dictates the potential error of an experiment. This experiment aims to demonstrate quality assurance through a standard hydrochloric acid solution of 0.1 moles per litre was used, and through titration of a sodium calcium solution, we can attempt to calculate the hydrochloric acid concentration after multiple experimental steps and determine the certainty of the method and appreciate the influence error has on a scientific analysis.

Methodology

To perform this experiment required a standard hydrochloric acid solution made via the preparation of constant-boiling-point hydrochloric acid. For the titration, utilize flasks with approximate 0.2 sodium carbonate each that is dissolved in a water solution alongside an indicator solution. Titrate the hydrochloric acid solution into each flask until the orange colour shifts to a faint pink recording readings as you progress.

Results

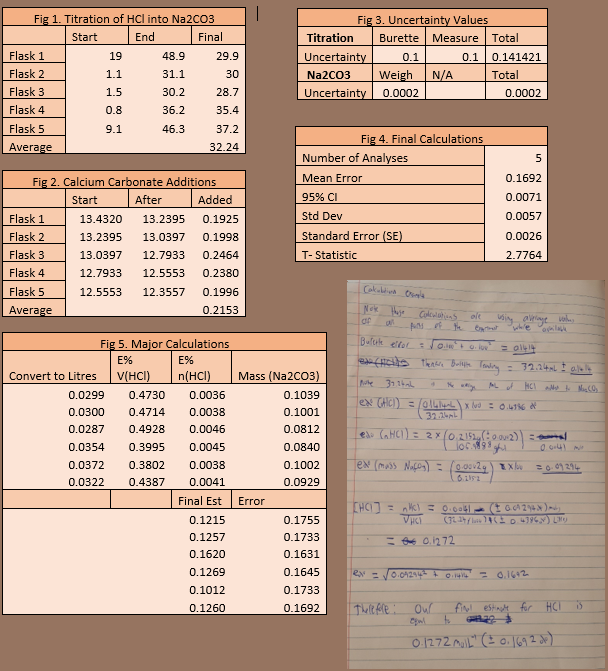

In the results of this experiment, there are two key elements in the experimental process which is the error of the equipment used. Experimentally, the flasks, weighing mechanism, and burette make up the values on Figure 3, the total uncertainty for these is approximately 0.1414, and 0.0002 (4dp).

Experimentally the amount of Na2CO3 in the flasks is shown on Figure 2 in the added column on average being about 0.2153g. Recordings of the ml of HCl added to the sodium carbonate solution can be found of Figure 1 with amounts added being approximate 32.24ml added on average. Based on the amount added up to the acid/base equivalence point, it was mathematically determined with consideration of error that the amount of acid calculated after the titration, differed from the original concentration of the HCl by a final estimate margin of 0.0001 mol L-1 (± 0.1692%) on average as shown on figure 4. This compared to the original 0.1 mol L-1 solution along outlines the significance of uncertainty and error as well as the complications that come with quality assurance.

Bibliography

Harris, D.C. Quantitative Chemical Analysis 7th Edition W.H. Freeman and Co., Freeman and Co., New York. ISBN: 0-7167-7041-5

University of Otago: Chemistry Department (2022). A Practical Course in Forensic Analytical Chemistry. 2022 Edition ed. University of Otago.

Vogel A. Vogel’s textbook of quantitative chemical analysis. Harlow, England : Prentice Hall, 2000, ISBN: 0-5822-2628-7

This report was written for the University of Otago in the paper CHEM306 over a two week long lab cycle.

Counterfeit foods are serious business politically, economically, and generally. Honey is a rich sugar and protein substance which is made differently across different countries through different methods. Although honey that is made to masquerade honey through addition of sugar adulterants do not follow these guidelines each honey is made by, manipulating its contents for cheaper alternatives, and passing them off as an authentic product Wiley Research, n.d. Because of this however, analyses can be used to differentiate between a legitimate and illegitimate honey product. Although notably the reason why this is important to test for, is counterfeit food goods can come with potentially dangerous impacts on the consumer, as honey is known to have many positive effects medically and nutritionally. Fraud foods therefore is subject to leading its consumers astray, potentially even being toxic to them Fakhlaei et al., 2020.

The adulteration of C3 sugars, which are derived from the nectar bees obtain from plants will differ from the adulteration of other sugars such as C4 sugars derived from cane sugar as well as high fructose corn syrup. This information is critical to routine determination of illegitimate goods and is what this experiment aims to analyze a selection of six different honey samples and observe through a pass or fail test between the adulteration of these sugars compared to reference whole honey standards. The honey analysis involves especially isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) to detect foreign sugars through carbon isotopes which is a commonly practiced testing method today Walker et al., 2022.

Methodology

Using a selection of different honey products, follow procedures outlined by the University of Otago Lab Manual for Forensic Chemistry of 2022. Each product was weighed and dissolved in water with heating, thereafter, centrifuged five times to clean and keep the floc. The left-over pellet was then dried and an isotope ratio analysis on the compound was done to derive adulteration data on each honey sample.

Results

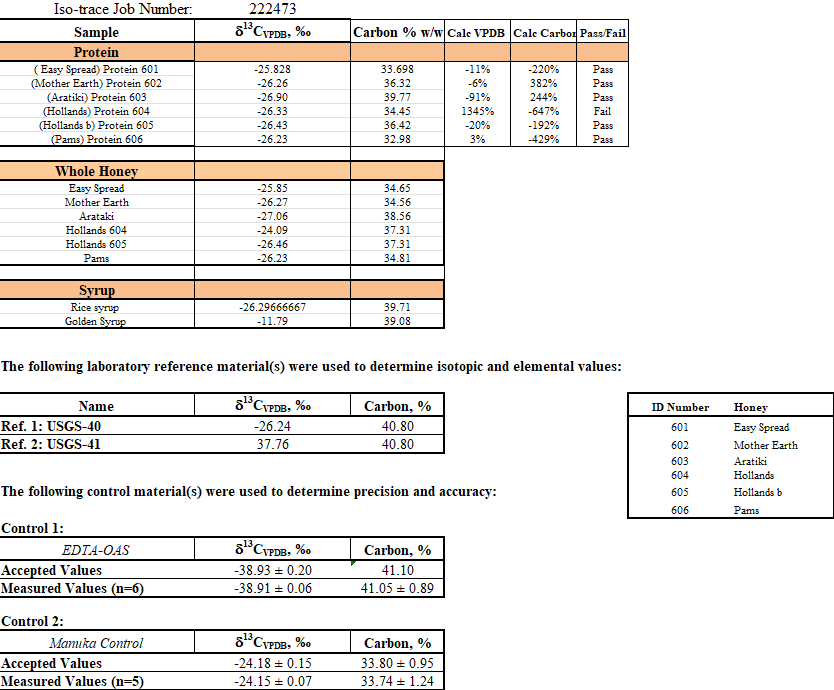

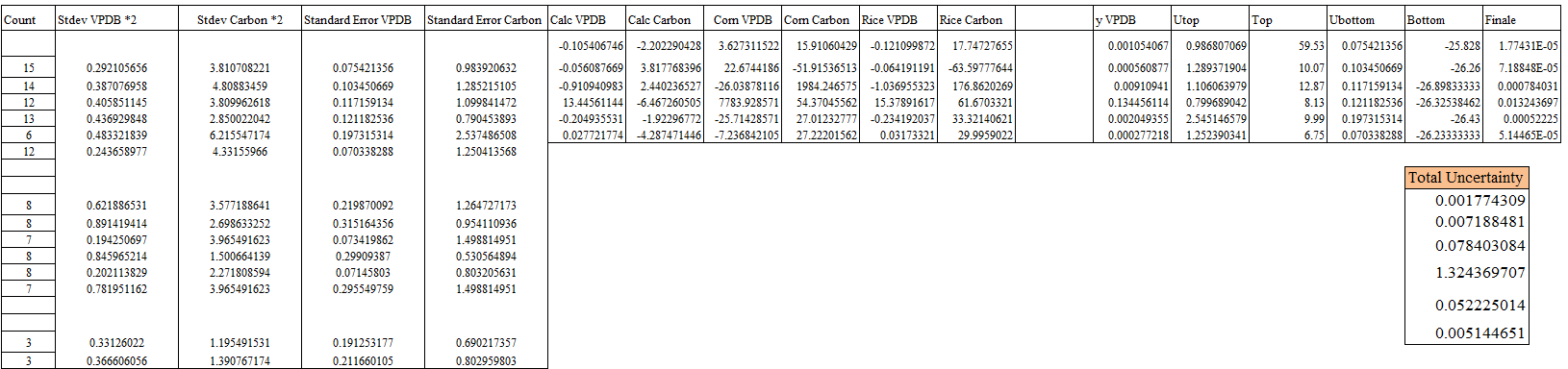

The results show a test of adulteration using a standard reference of whole honey products against the samples. Calculations on the table also used a punitive value for high fructose corn syrup to select for the C4 sugars and calculate for evidence of adulteration therefore indicating for substituent sugars being used in its composition. Any values that are only 7% approximately are indicative of adulteration in the samples, out of the tested samples only one honey, the Hollands Protein 604 failed the test showing evidence for honey adulteration.

In the context of possibility calculative uncertainty, total uncertainty for each honey sample were also deduced and can be applied in the formula:

% Honey Adulteration ± Total Uncertainty.

Although the status of honey passing or failing the test with the total uncertainty included does not change.

Calculation Working

Calculate the adulteration of 13C VPDB (Easy Spread) Protein 601 = ((-25.858 - -25.85)/(-25.828-(-9.7)))*100 = -0.105406746

and the adulteration of Carbon% = ((33.698 - -34.65)/(33.698-(-9.7)))*100 = -2.202290428

Standard Error of 13C VPDB = 0.2921/sqrt(15) = 0.07542

Standard Error of 13C Carbon = 3.8107/sqrt(15) = 0.9839

To calculate uncertainty, we use the equation y*(sqrt(((utop/top)^2)+((ubottom/bottom)^2)))

y = -0.1054/100 = 0.001054 (This is drawing from the adulteration of 13C VPDB

utop = 0.07542/0.9839 = 0.9868

top = 33.698 - -25.828 = 59.53 (Difference between carbon % and 13C VPDB)

ubottom = SE of VPDB = 0.07542

bottom = -25.828 (13C VPDB)

When put all together we have:

0.001054*(sqrt(((0.9868/59.53)^2)+((0.07542/-25.828)^2))) = 1.77431E-05.

We want to revert this by times 100. To get the total uncertainty

1.77431E-05 * 100 = 0.001774309

Bibliography

Fakhlaei, R., Selamat, J., Khatib, A., Razis, A.F.A., Sukor, R., Ahmad, S. and Babadi, A.A. (2020). The Toxic Impact of Honey Adulteration: A Review. Foods, 9(11), p.1538. doi:10.3390/foods9111538.

University of Otago: Chemistry Department (2022). A Practical Course in Forensic Analytical Chemistry. 2022 Edition ed. University of Otago.

Walker, M.J., Cowen, S., Gray, K., Hancock, P. and Burns, D.T. (2022). Honey authenticity: the opacity of analytical reports - part 1 defining the problem. npj Science of Food, 6(1). doi:10.1038/s41538-022-00126-6.

Wiley Research (n.d.). Honey Authenticity. [online] secure.wiley.com. Available at: https://secure.wiley.com/HoneyAuthenticity [Accessed 12 Aug. 2022].

This report was written for the University of Otago in the paper CHEM306 over a two week long lab cycle.

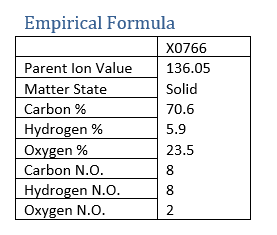

This report analyses the unknown substance X0766 by deduction from its empirical formula and determining the structure via NMR and IR spectroscopy.

To elucidate the structure of X0766 we need an empirical formula to base it off, we have been already provided with the percentages of elements in the substances as well as their parent ion molar mass, which were used to calculate the approximate empirical formulas of both substances which helps to begin putting together the substance structure. Using this, generally, carbons are bonded together with up to three hydrogens on the end carbons and 2 hydrogens on carbons along the chain. For X0766, this would mean we can expect 18 hydrogens for 8 carbons, but there are only 8 hydrogens, this can indicate for carbon-to-carbon double bond structures reduce the number of bonding hydrogens, possible ring structures of carbon bonds looping, and additional structural groups along the carbon chain. This also narrows the structure down to a benzene ring, consisting of six carbons but this leaves out the two other carbon groups as well as 4 hydrogens which are a part of some other structure group attached to the chain. Many of the methodologies to elucidate the structure was derived from the University of Otago: Chemistry Department 2022) among other useful chemical elucidation resources.

X0766 was then run through both 1H, 13C NMR spectra and IR spectra to visualise information about the structures. X0766 has two key NMR spectra for Carbons and Hydrogens.

Gmol C = 12 | Gmol O = 16 | Gmol H = 1

70.6/12 = 5.883 | 5.883/1.46875 = 4 | 4*12 = 48

5.9/1 = 5.9 | 5.9/1.46875 = 4 | 4*1 = 4 | 4 * 1 = 4

23.5/16 = 1.46875 | 1.46875/1.46875 = 1 | 1*16 = 16

Total = 48+4+16 = 68 | 68*2 = 136 which is approximately equal to parent ion value of X0766.

X0766 Formula: C8H8O2

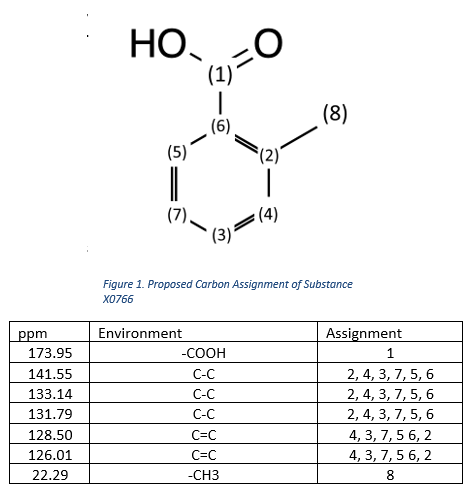

13C NMR Notes for X0766

The carbon 13 NMR spectrum (Figure 4) has 7 major peaks at positions 173.95, 141.55, 131.79, 133.14, 126.01, 128.50, and 22.29, all these peaks were analysed using Mestrenova. We should have 8 peaks so this means that one of these peaks may be split by obfuscating another similar structure in the peaks. The peak however at position 77.2 is the chloroform solvent peak and isn’t relevant to the examined unknown substance. Most of the methodologies and ideas used to interpret the 13C NMR data come from Clark (2014a) as well as the lab manual provided by the University of Otago: Chemistry Department (2022)

To start we can infer the substance we are working with is an aromatic compound due to the high abundance of peaks in the 100 to 160ppm range, which is a pattern often found with aromatic compounds.

Secondly, with the farthest peak at 173.95, peaks at this ppm range are consistent with carboxylic acid groups and esters. In addition to this, the earliest peak at 22.29 informs of another important structure, a primary alkyl group or methyl function group. Based on the allotment of carbon and hydrogen atoms we must elucidate this structure; all hydrogens and carbons would be inadequately accounted for had the structure had an ester functional group and therefore it is most probably a carboxylic acid group that accompanies the methyl group.

Lastly, in the assignment of carbons due to the high frequency of C=C and C-C groups, determining their exact assignment is difficult. Although the assignment for the functional groups is evident as they have the only unique environmental structures.

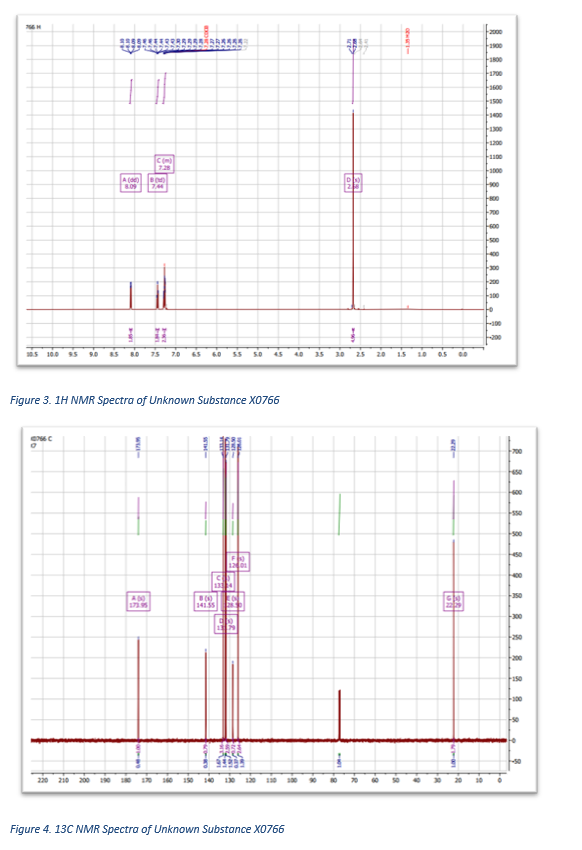

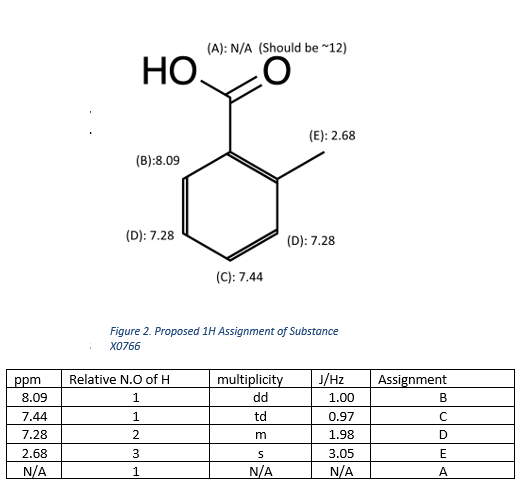

1H NMR Notes for X0766

With the 1H NMR (Figure 3), each peak was integrated, and the reference solvent peak was identified at 7.26ppm. Out of all the peaks, we found a double doublet at 8.09ppm, a multiplicity peak at 7.28ppm, a triplet doublet at 7.44 ppm, and one really large peak around 2.68ppm. All information here is analysed through MestreNova and interpretation information is largely derived from a helpful 1H NMR guide by Clark (2014b) alongside data from the lab manual provided by the University of Otago: Chemistry Department (2022)

Starting with the large peak at 2.68ppm, it is a methyl group as the peak is indicatively early in the spectra and contains a total of three hydrogen atoms in the group. One thing that is worth noting though, is based on the carbon 13 NMR, it was determined there is a carboxylic acid group on the substance, although the peak for this would be very small near to 12ppm which the spectra we obtained didn’t visualize possibly due to technological limitations, error, or a bad NMR generation.

Following this, we needed to determine the orientation of the methyl group from the carboxylic acid group on the substance. We knew though, that because there were two cases of symmetry on the NMR (two multiplicity detections) there was no way it could be in the para position. Using chemical shift of substituted benzene calculations, we found the position of the groups was determinable. For position B we found that the equation 7.27 + 0.85 = 8.12 was close to the peak found at 8.09ppm which tremendously helped in confirming the substance was in the ortho position. Because of the peak at 8.09, there were only two locations left for the split multiplicity peak that was shared between the two groups. These groups would have to be in a symmetrical position, and hence, the last possible position left for the methyl group to be in was position E.

The last position at C was concluded to be the peak at 7.44ppm through elimination, as there were no more outstanding peaks that were unaccounted for in the NMR.

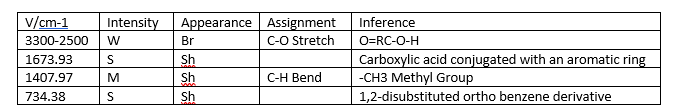

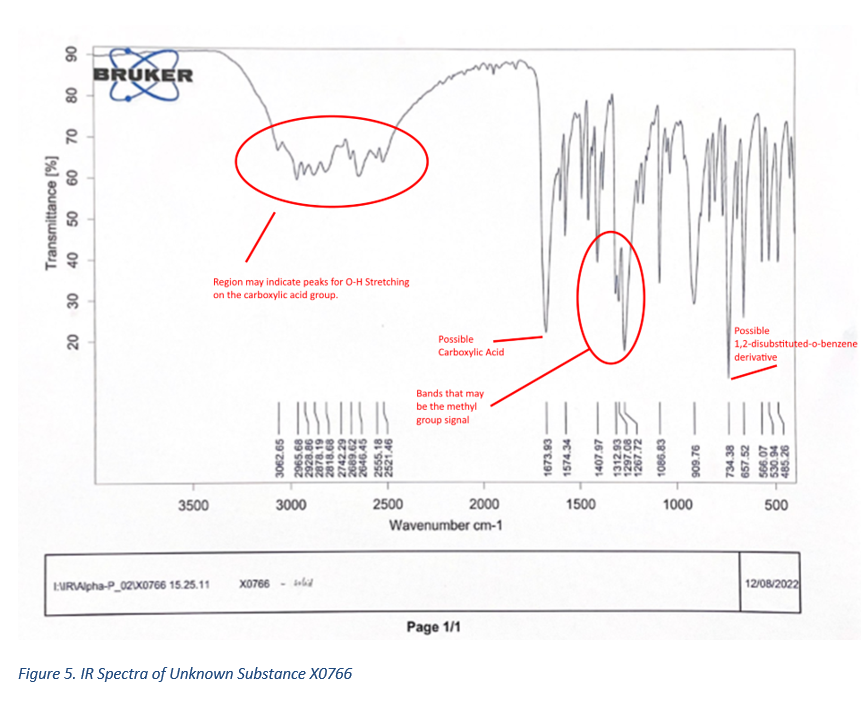

Notes for X0766 IR Spectra

The IR spectra help reinforce or infer some of the possible structures of the unknown substance X0766. It is worth mentioning, however, that the IR spectra aren’t entirely concrete, as detected spectra as well as the position of spectra can vary relative to the structure group. On this IR in particular this may very well be evident. Some of the IR spectra inferences that have been made come referred from both the resources from Ashenhurst (2019), and the University of Otago: Chemistry Department (2022) Lab Manual.

With what we already know from the carbon 13 NMR and the indicated carboxylic acid region, we can see an IR band at the point 1673.93, which is very close to the wavenumber range of 1700-1680, a general location where can infer a possible carboxylic acid conjugated with an aromatic ring. This helps us identify, that while it is not perfect in range, this is possible the band for these elements inferring again the substance is an aromatic compound and has a carboxylic acid group. To add to this, the wavenumber range of 3300-2500, while is a very big range, can also infer O-H stretching on a carboxylic acid group, but the bands in this region are very broad.

Another band on the IR spectra shows a lone band at 734.38. This band is close to 755, the absence of multiple bands in this region and close to wavenumber 755 could indicate that the structure is a 1,2-disubstituted ortho benzene derivative which reinforces what was concluded in the hydrogen NMR analysis of the structure functional group positioning.

The last band worth noting on the IR spectrum is the methyl group, but strangely the expected range of 1355-1395 as well as 1430-1470 is absent. Although there is a band at 1407.97 with a smaller band which could be the methyl group, albeit wouldn’t be easily determinable without other analytical resources such as the NMR.

Conclusion of Elucidation

In finalization, I believe I have accurately deduced that the unknown substance named X0766, is in fact a compound known as o-Toluic Acid. An aromatic compound that is made up of a benzene ring, a carboxylic acid group, and a methyl group in the ortho position from the carboxylic acid. I also have additional confirmation that my assertion that this is toluic acid based on the AIST database (AIST 2019) which contains NMR and IR spectra data that closely parallels the spectra I had generated.

Summary

We were represented with an unknown substance labelled as X0766, it was a solid substance that was white, flaky, and had a strong flowery aroma. I and my lab partners had to determine what the substance was. With the substances we were provided molecular information that describe the percentages of different elements in the substance. Using these we were able to mathematically calculate an approximate empirical formula that for sample X0766 consisted of 8 carbons, 8 hydrogens, and 2 oxygen atoms. The formula of this compound aid significantly in understanding the structures of the unknown substance. The next step involved scientific spectra machines to generate an infrared (IR) and two nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrum graphs for each substance. The IR spectrums we generated can compare to known IR patterns for different structures of substance which helps identify some of the structures in the substance based on the number and size of the bands. The NMR spectrums help not only to confirm the observations that are made from the IR spectrums but also to determine chemical shifts and locations of structure on the unknown substance. Peaks on the NMR for each graph generated call for carbon-13 isotopes and hydrogen-1 isotopes which helped us determine two key structures, a carboxylic acid group of C-COOH, and a methyl group of C-CH3.

After figuring out the structure, we determined the unknown substance was ortho toluic acid or o-toluic-acid, which we then confirmed after checking online databases of spectra that paralleled the IR and NMR spectrums we had made.

Bibliography

AIST 2019, AIST:Spectral Database for Organic Compounds,SDBS, Aist.go.jp.

Ashenhurst, J 2019, Interpreting IR Specta: A Quick Guide – Master Organic Chemistry, Master Organic Chemistry.

Clark, J 2014a, interpreting C-13 NMR spectra, Chemguide.co.uk.

― 2014b, the background to nuclear magnetic resonance (nmr) spectroscopy, www.chemguide.co.uk.

University of Otago: Chemistry Department 2022, University of Otago CHEM306 Lab Manual.

This report was written for the University of Otago in the paper CHEM306 over a two week long lab cycle.

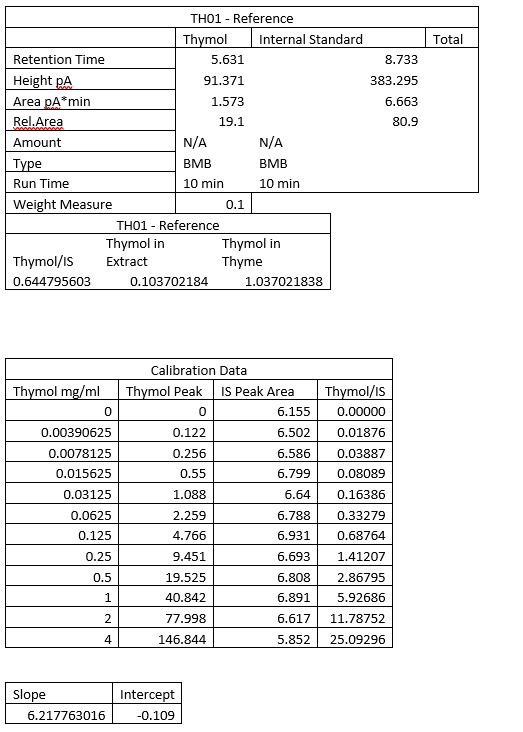

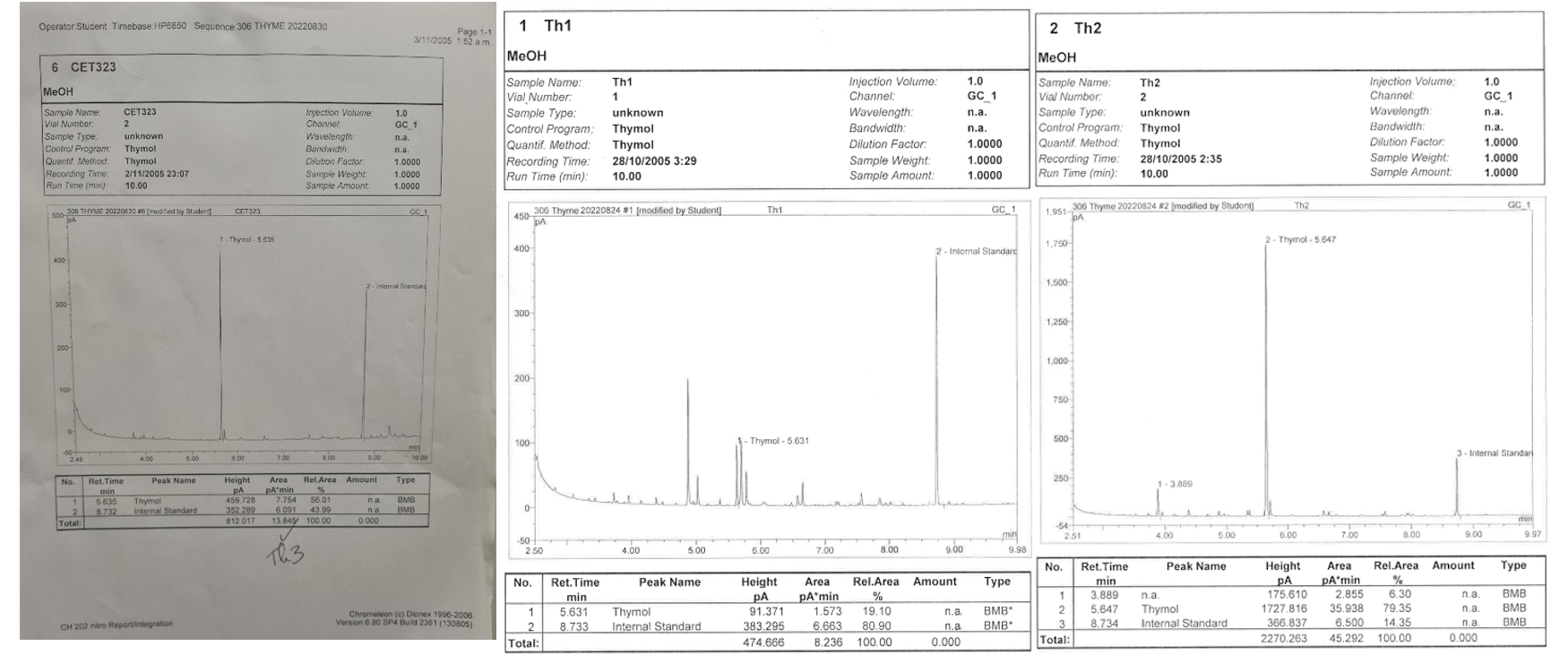

In this analysis, we aimed at doing a gas-phase chromatography analysis on three variant cooking herbs called thyme, which in particular is a herb rich in thymol. Using this analysis, we want to elucidate the variable quantities of thymol among different samples as a routine client checkup using the procedures from the laboratory book provided University of Otago: Chemistry Department (2022).

Methodology

The gas-chromatography used had the following configurations:

Model: Agilent 6850, HP-1, 30m, 0.320nm.

Column type: 0.25mm film

Carrier Gas and Flow Rate: Helium 1.9mL/min

Injection Volume, Temperature, and Injector Split: 1 microlitre, 270 degree Celsius, 10:1 split.

Column Temperature Programme: Finish temperature of 250 degrees Celsius with a start temperature of 50 degree Celsius. Rate of temperature increase was 20 degree Celsius a minute.

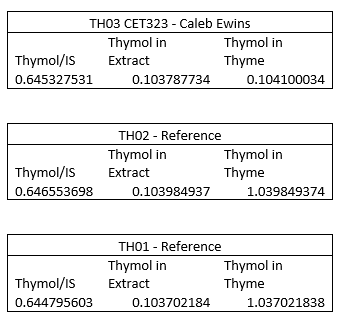

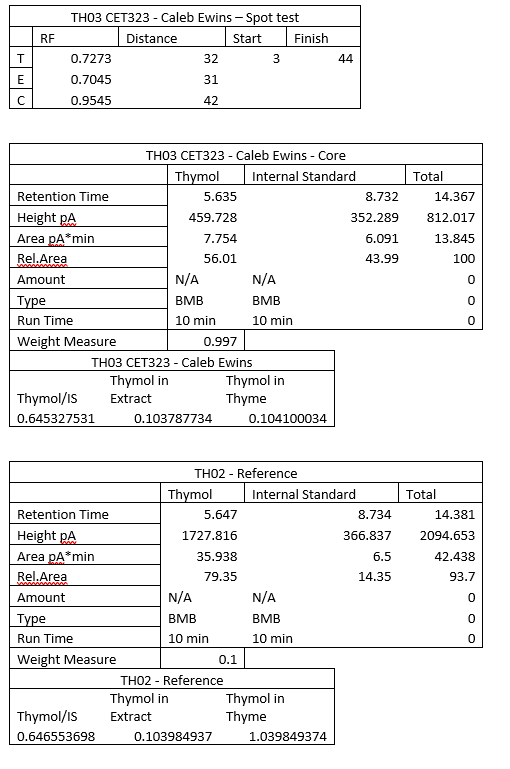

The amount of thymol used in this analysis was approximately 0.1 grams. However, CET323 TH03 was incorrectly weighed and instead is comprised of 0.997 grams.

Results

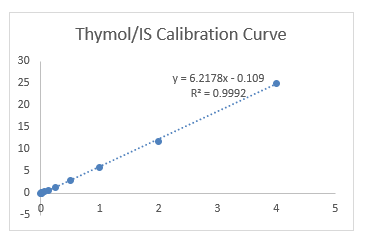

The calibration curve was calculated out of a selection of 18 different calibration tests using thymol and the internal standard solution. The calibration tests have notable features worth considering though. Some of the calibrations have broad peaks, indicating some of the analyte was moving more than others, ideally a a narrow peak is what we want, as this disturbs the precision of the experiment. Another issue that was noticed in some of the calibrations was forwarding peaks likely as a result of overloading the analyte.

Accordingly, the concentration isn’t massively difference across the samples with the exception of TH03. The reason for this though, is the amount of thyme used in CET323 was 0.997 grams as opposed to what was supposed to be 0.1 grams. Generally, though, the concentrations of the samples very similar which reflect their retention times across each GC chromatographical test.

Accordingly, the concentration isn’t massively difference across the samples with the exception of TH03. The reason for this though, is the amount of thyme used in CET323 was 0.997 grams as opposed to what was supposed to be 0.1 grams. Generally, though, the concentrations of the samples very similar which reflect their retention times across each GC chromatographical test.

Calculation (Using CET323 - TH03)

Thymol/IS = 5.563/8.732 = 0.6453

Approximate Thymol in Extract = (Thymol/IS) divided by the calibration slope = 0.6453/6.2178 = 0.1038

Approximate amount of Thymol in the Thyme = 0.1038/0.997 = 0.1041

Summary

We were provided three different thymol samples labelled TH01, TH02, and TH03. These were ran through a chromatogram against an internal standard to discern their thymol concentrations. The concentrations were found to be similar although TH03 was incorrectly weighed as instructed by the laboratory procedure. In order to accurately calculate the thymol as well, a calibration curve was made out of 18 calibration tests of which some had some notable gas chromatography structures relevant to obstruction of accuracy such as peak broadening and overloading.

References

University of Otago: Chemistry Department (2022). A Practical Course in Forensic Analytical Chemistry. 2022 Edition ed. University of Otago.

Appendix

This report was written for the University of Otago in the paper CHEM306 over a two week long lab cycle.

Since the advent of modern-day forensic testing of DNA, a great potential of information was attainable in pursuit of solving crimes that formerly, were not solvable by the methods of the time. But DNA on its own poses its own challenges and despite its perceivable preciseness in identifying individuals, laboratory limitations find uncertainty to be a continually reoccurring and troubling factor in forensic testing. The DNA Database called the Combined DNA index system (CODIS) is one of the widely known forensic programs that aims to utilize this DNA forensic testing and revolutionize forensic analysis. CODIS does this by implementing a database of DNA fingerprints that function off a selection of 13 different DNA markers called short-tandem repeats (STRs), these STRs are heritable and shared among local communities, but to share every single locus is probabilistically unlikely and henceforth is heralded as an effective means of identifying a unique DNA fingerprint of individuals. Crime scene DNA evidence used by the FBI is typically stored in the CODIS system and DNA collected from suspects is collected and run through their database to find any hits for a corresponding DNA fingerprint in their whole database (FBI n.d.).

As a general overview, DNA databasing has become a part of forensic testing because of its specificity in identifying a criminal. The idea is that as more information is logged into the database the higher the chances to solving a crime with the database, but therein lies a single problem, the unlikely scenario where a DNA database makes a DNA hit for the wrong person which varies from country and country based on the database they are in use of. Additionally, there are major considerations to be had as to whether it is wise to push legislation and policy to enforce these databases unto offenders including young children. The UK for instance tried to push their DNA database forensic tools further with an emphasis on solving crimes despite gathering innocent people’s data, and after public push back the idea was discarded with many new questions being raised on the human rights considerations and ethics that come with a DNA database program (Wallace et al. 2014). As for the effectives of these databases however, especially in cost and accessibility, new techniques are consistently being founded in order to best optimize the DNA databasing system for forensic analysis while maintaining reliability in the methodology. A notable statistic however, in database effectives as of 2021 found that developed databases from countries such as the UK and NZ that have played roles in nearly 70% of cases that were unsolved. Cost-wise too, it has shown that DNA database methods can be cost effective on a case-by-case basis but is not always successful in forensic analysis. And with more and more countries developing their own DNA databases its easy to see there is a great demand, and reportedly a good investment benefit to the inclusion of DNA forensic testing across the world (Wickenheiser 2022). However, this should not obfuscate the shortcomings of DNA testing, let alone its involvement in failure to impose just justice.

DNA Databases though have not just seen used in solving crimes though, but it has too also caught ire for their occasional involvement in a miscarriage of justice in the law. According to Cassell (2018) approximately in America, the wrongful conviction rate is turbulent, in that some claim it to be as low as 0.027% or sit in a range of 0.016% to 0.062%. Some sources argue, however, that the rate is as high as at least 1% and above. This is a crucially important statistic to understand given the challenge to provide just judgement and legal enforcement because miscarriages of justice do happen. Such as in the case of Raymond Easton, and at the time 49-year-old advanced Parkinson’s afflicted citizen who by chance claimed to be a 37 million to one chance had their DNA to match evidence DNA linked to a break in miles away. Raymond was arrested, and after some deliberation in court, a duplicate DNA test was done that cleared Raymond from the crime with the conclusion as to how this happened to be contamination in the lab the DNA testing was done in (The Herald 2006). But this alone is not the only application DNA testing has found, as it has also seen used inversely to exonerate people in the eyes of law with new-found evidence. DNA offers an important insight into how this wrongful conviction rate could be overturned, as DNA evidence is also technically useful to generate evidence in favour of the innocence of the defendant. For instance, in the case of a death row prisoner discussed by Steinbuch (2021), a man called Thibodeaux spent 16 years convicted after an accusation of rape and murder of their cousin. The man in question, during the investigation, had initially denied it until eventually giving in to the interrogative practices and falsely confessed only many years later to have been exonerated after a new piece of evidence through DNA analysis came out that pointed toward his innocence as Thibodeaux’s DNA was not linked to the rape that had occurred with the cousin.

When DNA evidence does work however it does have results to show for its effectiveness in supplementing evidence against a suspect and even solving criminal cases that have gone cold and without leads. For instance, DNA testing was key to solving a double homicide in 1956 65 years after its occurrence. This case was originally reported in Texas by three boys who came across the dead bodies of a teenage man and woman victim of a homicide involving a firearm with evidence to suggest a sexual assault had occurred. The victims, Bogle the 18-year-old male victim and Kalitzke the 16-year-old female victim had DNA information among other content stored after their autopsy; A history was also generated that found the two victims were lovers. The case had not led only up until one of the DNA samples collected in the form of a vaginal swap from Kalitzke, found sperm DNA that wasn’t her boyfriend, Bogle. They ran the DNA with the intention of at the least constructing a family tree, their testing led them to conclude the DNA belonged to a man called Kenneth Gould, a husband with children that had passed in 2007 (Pruitt-Young 2021).

Weaknesses

• DNA evidence that is present at scene could also be planted evidence by the offender, or unintentionally from an unaffiliated party.

• Retrievable DNA varies and generally only attainable in small amounts.

• DNA is subject to change in the event of mutation overtime, or even during collection resulting in subsequent added profiles, or old profiles to become obsolete

• Mishandling and misuse of DNA is possible.

• Different agencies and organizations may use different means of storing DNA information to others, meaning compiling a whole database or shared database for a largely globalizing world may be an obstacle.

• Major ethical concerns or privacy concerns.

Strengths

• Helpful in supplementing physical evidence to confirm presence, involvement, or possession of an item or location of interest.

• Helpful in supplementing other DNA related studies.

• Outlines useful populational data.

• Every person has a DNA fingerprint, which generally speaking unless they’re twins, is unique to the person expect in very unlikely circumstances. As more DNA processing tools are introduced, presumably the resolution increases.

As I see it, DNA databases pose a serious threat and concern to the privacy of people, but they are not without uses and purposes that outweigh some of the cons. Forensic analysts are constantly challenged by new problems that require new solutions, it would be a disservice to claim any one piece of evidence as being absolute evidence of criminal activity, but it helps to have a variety of tools to further close the gap of uncertainty in identifying an offender. This is where a quandary arises, as I believe DNA databases have their uses in crime scene analysis, but personally to just give DNA to be logged into a database crosses severe concerns of privacy, ethics, and additionally concerns for future applications and advancements relative to DNA data. To put it, given the disproportionate amount of crime by marginalized groups for a variety of reasons ranging from political to socio-economic, this disproportionality would reflect in a DNA database as well, which would mean it would only serve to impact those marginalized groups more (Ahmed 2019). If I cannot hold myself to the standard that I would not want that to happen to me, it cannot happen to anyone else. Although, there is one caveat to giving contributing personal DNA for a database, and that is if I personally were a suspect, and whether, after it has been concluded I am non-suspect, that the data collected be expunged from the database but this choice to donate to a database for this temporary use I stress is a decision by the donator.

DNA databases are not without uses, but it is far from infallible. It would be unwise to not use the technique, and when used it should be used to supplement a criminal investigation of more evidence albiet with awareness and scrutiny for it.

References

Ahmed, A 2019, Ethical Concerns of DNA Databases used for Crime Control | Bill of Health, Bill of Health, viewed 3 September 2022, https://blog.petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/2019/01/14/ethical-concerns-of-dna-databases-used-for-crime-control/>.

Cassell, PG 2018, Overstating America’s Wrongful Conviction Rate? Reassessing the Conventional Wisdom About the Prevalence of Wrongful Convictions, papers.ssrn.com, Rochester, NY, viewed 1 September 2022, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_i=327618.

FBI n.d., CODIS and NDIS Fact Sheet, Federal Bureau of Investigation, viewed 3 September 2022, https://www.fbi.gov/resources/dna-fingerprint-act-of-2005-expungement-policy/codis-and-ndis-fact-sheet>.

Pruitt-Young, S 2021, Detectives Just Used DNA To Solve A 1956 Double Homicide. They May Have Made History, NPR.org.

Steinbuch, Y 2021, Wrongly convicted man who spent 15 years on death row dies of COVID-19, New York Post, viewed 11 May 2022, https://nypost.com/2021/09/14/wrongly-convicted-man-who-spent-years-on-death-row-dies-of-covid/>.

The Herald 2006, Guilty by a handshake? Crime-scene DNA tests may not be as accurate as we are led to believe, The Herald: Scotland, viewed 1 September 2022, https://www.heraldscotland.com/default_content/12440889.guilty-handshake-crime-scene-dna-tests-may-not-accurate-led-believe/>.

Wallace, HM, Jackson, AR, Gruber, J & Thibedeau, AD 2014, ‘Forensic DNA databases–Ethical and legal standards: A global review’, Egyptian Journal of Forensic Sciences, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 57–63.

Wickenheiser, RA 2022, ‘Expanding DNA database effectiveness’, Forensic Science International: Synergy, vol. 4, p. 100226.

This essay was written for the University of Otago in the paper MICR336 with an expected word count of 2000 plus or minus 10% with a total of ~2008 words. There are 7 references used for this essay.

It is known in nature and in history, the occurrence of fire has been a topic of particular discussion, both in man-made fires and the more increasingly concerning frequency of naturally occurring fires and how they affect their environments. It is important to question the severity of these fires on the microbial level, and how environmental changes invoke certain microbial responses as well as examine how these microbial responses shape the environment they inhabit. However, sources of fire differ, as do the atmospheres, climates, and environments that are burned. So exactly, what environmental factors have a significant impact or trend indicative of burn and microbial response?

While environmental factors differ from locale to locale, research seems to suggest that heat as a microbial and environmental disturbance, especially heat derived from a fire makes changes to plant and soil characteristics which can both give rise to new kinds of microbial communities and overall changes in the environment. These characteristics are directly tied to the degree of heat and burn severity. Some of the commonly examined alterations that burn causes in microbial environments and communities are changes to soil pH, various nutrient resources, and elimination of microbial communities that perished to the burning opening potentially new microbial opportunities (Adkins et al. 2020). As a result of these changes in these microbial environments from burns, there is a suggestion that different native and non-native microbial communities may out-compete different species under these stresses which also in turn have implicit consequences for plant and fungal growth in the region (Hebel, Smith & Cromack 2009). Some taxa both fungal and bacterial have been found in other lines of research that seem to work as “fire responders” that were abundant and identifiable after a fire. There had also been notable recordings of post-fire taxa using the resulting carbon resources and changes to the nitrogen cycling of the soil that may have positive effects on plant growth (Whitman et al. 2019).

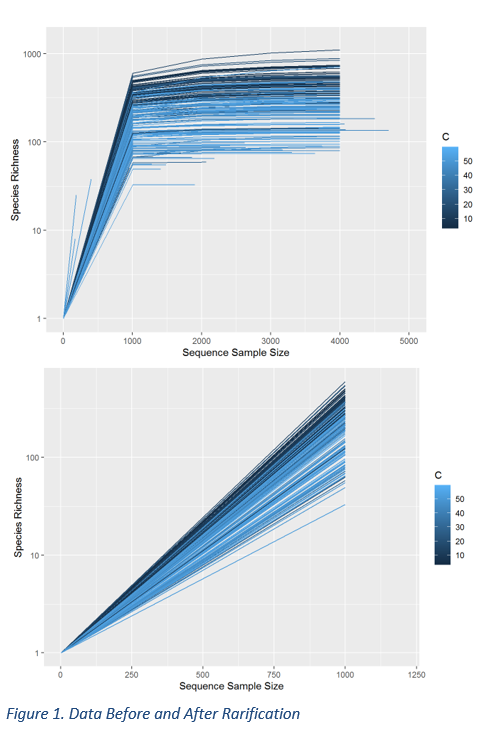

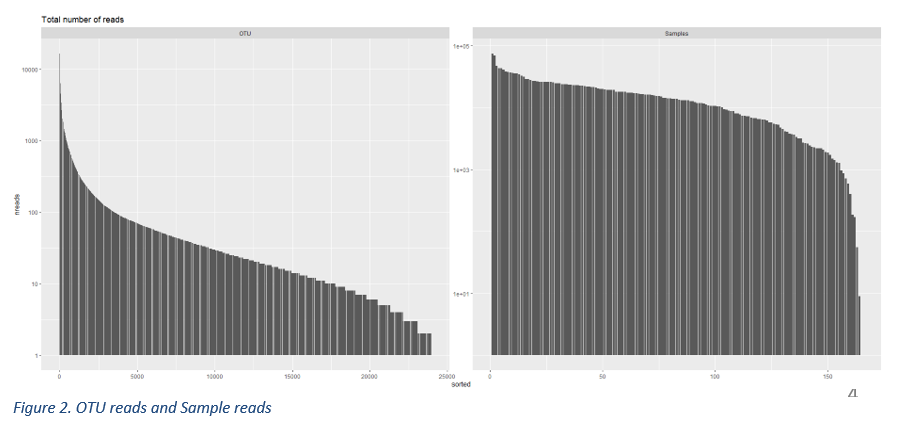

Microbes that come to grow into these communities thereby either thrive or struggle against the newfound conditions, which is important and key to understanding the effects of burns in the wider environment. Given modern-day implications of increasing wildfire breakouts as well, understanding the patterns and long-term effects of a burned environment and how microbial communities function within those conditions may be pivotal to wider scientific applications of these observations. The aim of this analytical report is to use plant burn data sourced from an article by Dove et al. (2021) to outline and identify patterns that are potentially indicative of microbial response to plant burn disturbances and determine which phyla are responsible for this response.

- N.O. of Samples: 165 (Pruned to 162)

- Treatments/Variables: 36 Sample Variables)

- Number of OTUs identified: 23955 Taxa of 8 Taxonomic Ranks)

Hypothesis: The status of plant burn acts as a stressor that invokes microbial response through changed in the nutrient environment and uptake of carbon pool resources and the carbon can be used as an indicator of these respondent microbes.

Null Hypothesis: The status of plant burn acts as a stressor that doesn’t invoke a microbial response through changes in the nutrient environment and uptake of carbon pool resources and the carbon resource cannot be used as an indicator of these respondent microbes.

Methodology and Results

For this analysis, the dataset originally was comprised of 165 samples until it was firstly pruned to remove all sequences in the data that were less than 100 sequences. This is done so that the data points of interest are the only data to be used. Once pruned, the data was then rarefied ending with a sample size of 162.

As shown in figure 1, the species richness rises up until the sequence sample size hits about 1000 in size. Hence the rarefication was revised at a rarefaction depth of 1000, where richness stops rapidly increasing. The total number of reads for the OTUs as well as the samples are depicted in Figure 2 which shows that the sample data covers ranges near up to 25,000 with nreads as high as 10,000.

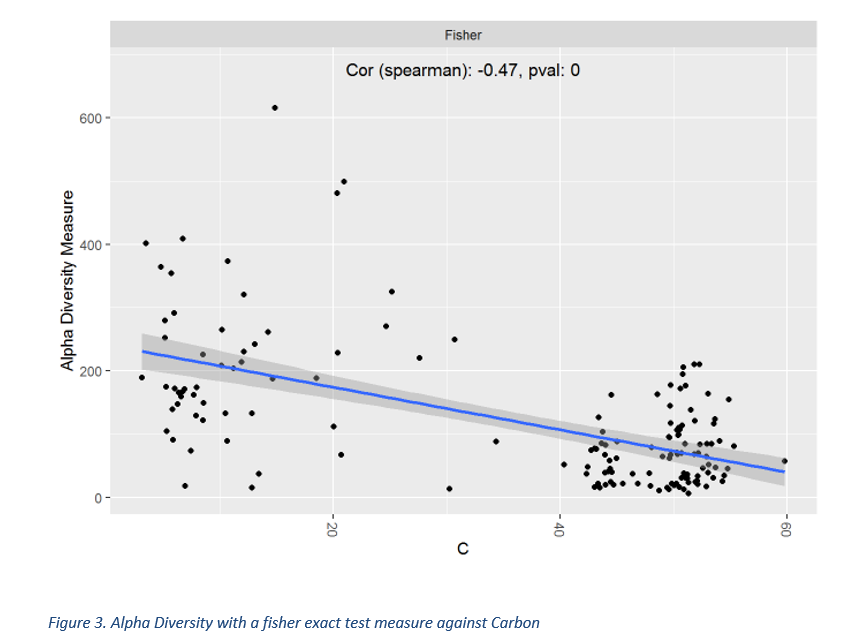

Alpha Diversity

The alpha diversity of the data was determined using a fisher exact test with a spearman correlation denomination. On figure 3, immediately evident is two different clusters of data with an approximate spearman correlation equal to -0.47. This indicates a relationship between the alpha diversity measure against the carbon quantity measure in which as alpha diversity decreases, carbon quantity increases. The P-Value of the fisher test is according to calculations equal to 8.962e-10 and rounded to 0 on the figure. This P-Value is significant in indicating that there is a relationship in alpha diversity between two different populations relative to carbon levels.

Beta Diversity

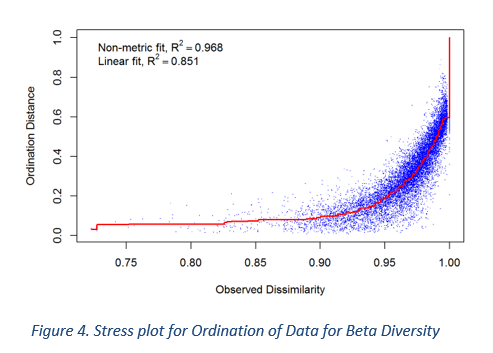

To begin with Beta diversity, we started with generating a stress plot to visualise the scattering of the data to see if the data appropriate fits in ordination as shown in figure 4. By using a binary test, it was discerned the stress lies at 0.1795 which according to ordination guidelines outlined by Clarke (1993) is within usable ranges.

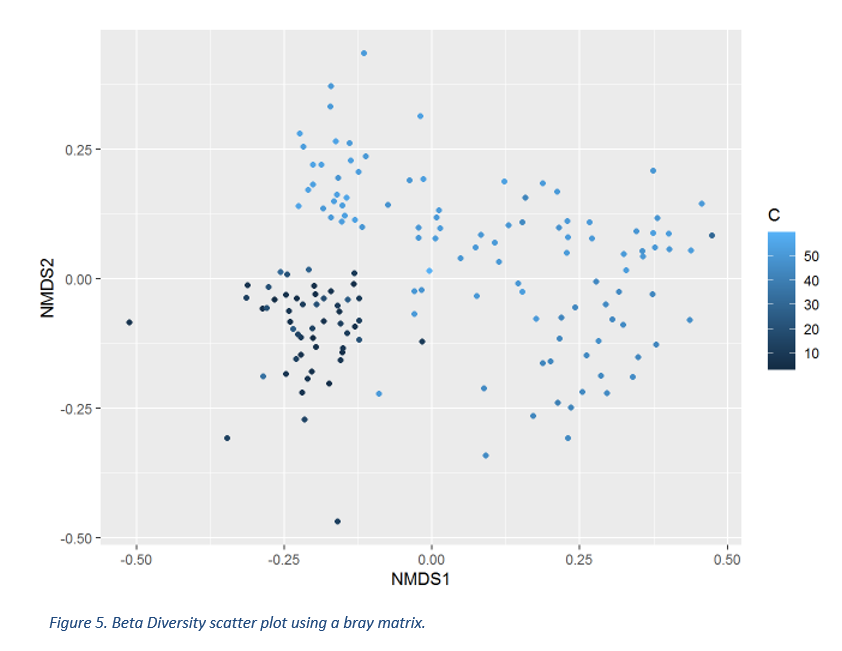

The beta diversity data was plotted along a non-metric multidimensional scaling plot against a bray dissimilarity matrix as shown in figure 5. Similarly, to the alpha diversity test, there is clear clustering of samples low in carbon content with a lot of scattering for higher carbon content samples.

The beta diversity data was plotted along a non-metric multidimensional scaling plot against a bray dissimilarity matrix as shown in figure 5. Similarly, to the alpha diversity test, there is clear clustering of samples low in carbon content with a lot of scattering for higher carbon content samples.

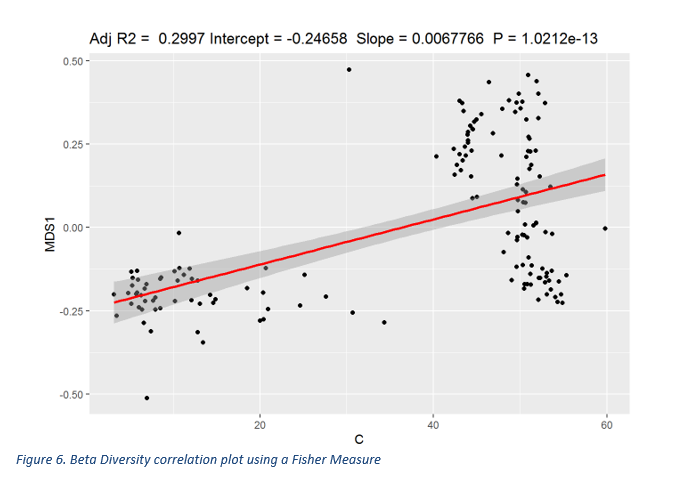

Lastly in Figure 6, again we can see two different clusters of data for both low carbon pools and high carbon pools. Also again, we can see a clear trend and correlation that as MDS1 increases, as does the carbon levels in the samples with a P-Value much lower than 0.05 indicating a strong significance that there is a relationship for the microbial groups relative to carbon pool levels between communities in beta diversity.

Lastly in Figure 6, again we can see two different clusters of data for both low carbon pools and high carbon pools. Also again, we can see a clear trend and correlation that as MDS1 increases, as does the carbon levels in the samples with a P-Value much lower than 0.05 indicating a strong significance that there is a relationship for the microbial groups relative to carbon pool levels between communities in beta diversity.

Comparisons of Taxa

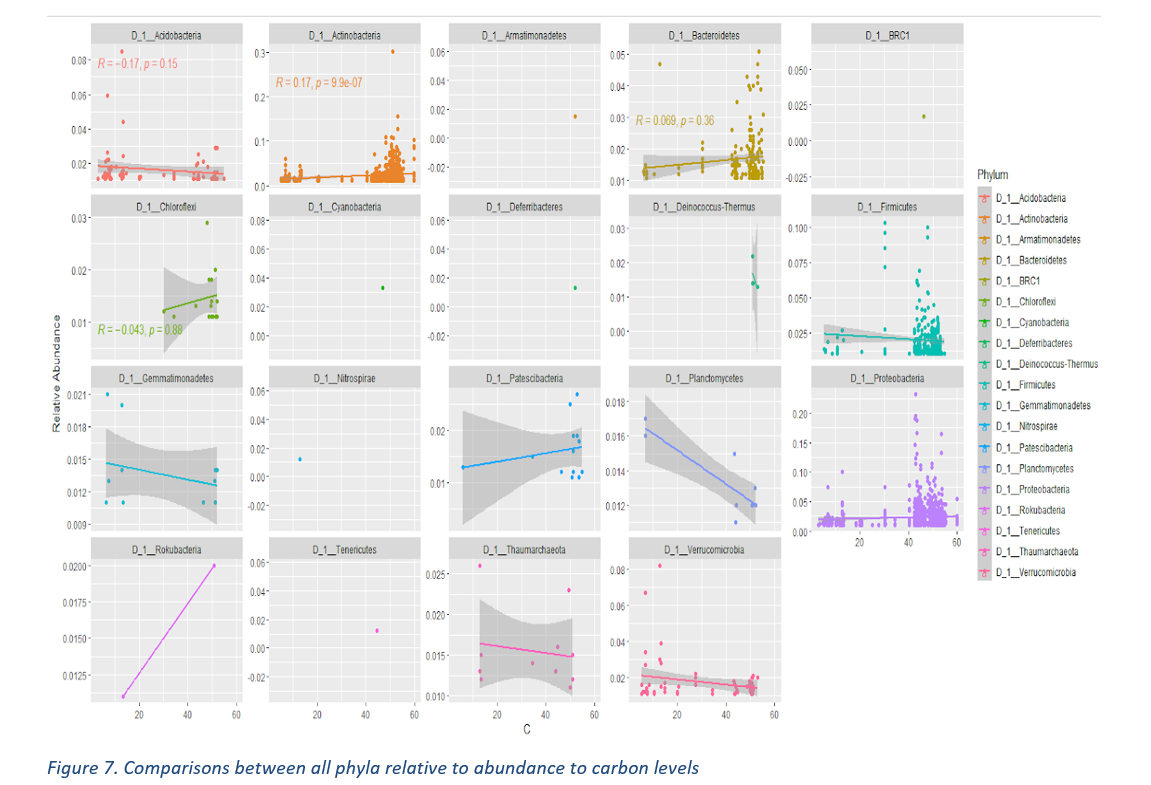

Figure 7 shows the community composition comparisons by phylum plotted against their relative abundance to carbon levels for the test. Of the 18 different phyla groups, there are some clear communities that are low in abundance with other groups indicatively being more variable and plentiful. Of these groups, we can see that Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Acidobacteria seem to be the more taxonomically relevant phyla of the data. These abundant phyla as well seem to have more data points clustered in high carbon levels with fewer in lower carbon levels, although Acidobacteria is very spread out compared to the other more abundant phyla.

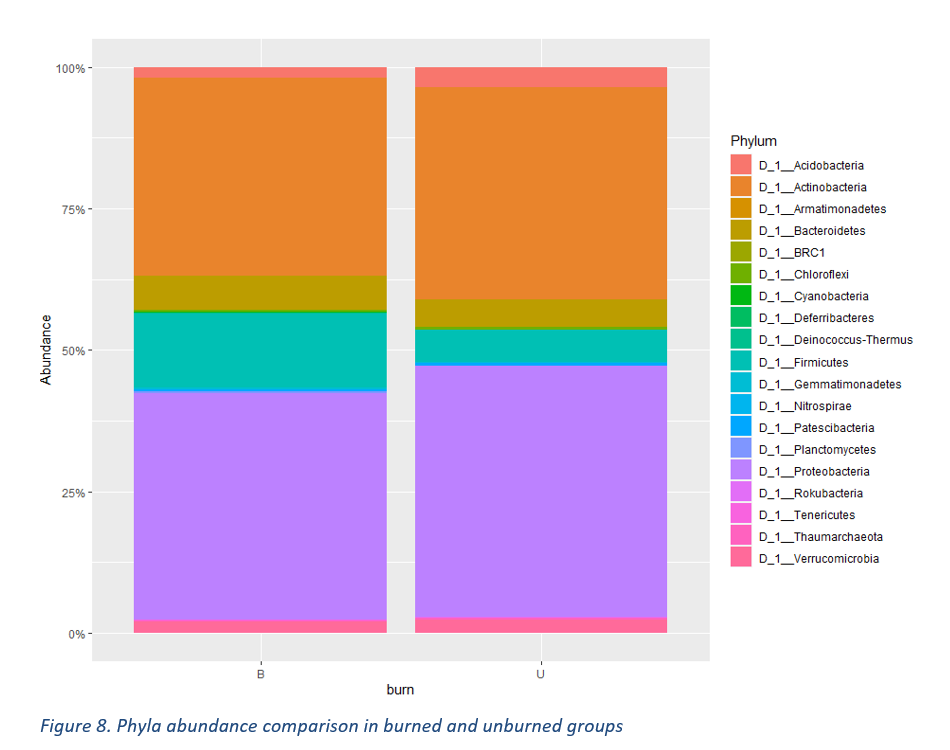

Following on from the phyla comparisons, based on the level of burn too, we can see which of the phyla are more common. Based on Figure 8, one observation for acidobacteria is that is not that prevalent and decreases in abundance when subjected to burn. Although Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria are very dominant compared to other phyla groups and seem to be non-affected or even grown in a burned environment as opposed to being in an unburned environment. With consideration of the variability of carbon levels across different phyla, we can determine that the microbial communities of Bacteriodetes, Proteobacteria, Firmicutes and Actinobacteria are the key communities of interest in surviving, and potentially growing after plant burns through the use of carbon pool nutrients thereafter the burn.

Following on from the phyla comparisons, based on the level of burn too, we can see which of the phyla are more common. Based on Figure 8, one observation for acidobacteria is that is not that prevalent and decreases in abundance when subjected to burn. Although Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria are very dominant compared to other phyla groups and seem to be non-affected or even grown in a burned environment as opposed to being in an unburned environment. With consideration of the variability of carbon levels across different phyla, we can determine that the microbial communities of Bacteriodetes, Proteobacteria, Firmicutes and Actinobacteria are the key communities of interest in surviving, and potentially growing after plant burns through the use of carbon pool nutrients thereafter the burn.

Discussion

Concerning the phyla comparisons, it is evident that some bacterial groups are not affected negatively, and instead remain or grow because of burn. There are a few reasons why this might be the case. In the event of plant burn, it introduces a stressor on the environment that affects the microbial communities of the plant and soil. In theory, microbial communities that are either fire resistant, or resourceful of the products of a plant burn are likely to thrive over microbial communities that are not as capable. In addition, the burn of the environment will result in none surviving communities being reduced or expunged any competition of the environment, which offers opportunities to the surviving microbes to further grow and take off from the resources circumventing any obstacles that otherwise would have been preventing for the microbes (Adkins et al. 2020). This would mean that the phyla such as Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes might be subject to this effect as hence why their abundances are either unchanged or greatened after the event of plant burn.

This finding would seem to reinforce some findings from previous studies of this same phenomenon, some of the abundant phyla observed in this report have positive responses to fire induce stresses and burns according to Adkins, Docherty & Miesel (2022). Some phyla groups they found tend to have a high abundance in post-fire conditions as a result of the microbial community changes and environmental changes much like this report. Actinobacteria and Firmicutes for instance are generally heat-resistant taxa that can form spores, and therefore can survive burn stressors. Bacteriodetes and Proteobacteria on the other hand respond to fire as more nitrogen and carbon become available nutrients. However, these bacteria and their successes are largely predicated on the severity of the burn and the pool amounts of nutrients in the microbial biomass. Curiously though some research seems to indicate the different types of woodland and trees tend to cause unique variations in the nutrient pools. In addition to this insight, microbial activity was shown to increase proportionally to changes in the soil and microbial biomass of Carbon as well as Nitrogen (Singh et al. 2021).

To conclude from the findings of this report, it is evident based on our data, that there is a response mediated by forest burn that particularly gives rise to microbial communities, and these new communities especially of the Proteobacteria and Bacteriodetes tend to use nutrient resources on and in the soil after the burn such as carbon to facilitate their growth after surviving plant burn circumstances. Given the significance of the alpha and beta diversities as well as the clear differences in carbon-heavy clustering and abundance differences relative to burn; the null hypothesis can be rejected as burn seems to invoke a microbial response via changes in the nutrient environment, and the uptake of those changes in the form of carbon pool resources is a useful indicator for burn-responding microbes. As such this both reinforces and puts forward there are microbial communities that respond to burn through increased carbon uptake which in turn will have sequential effects on the environment of those microbes.

Future Research

Given the rising concerns with worldly phenomena such as climate change as well as the installation of institutions on or the destruction of landscapes, there are a variety of unique variables that may be integral to furthering our understanding of microbial responses to burn. One of the major considerations that might be important is the distinction between sources for what causes a burn such as man-made fires via fuels and oils versus naturally occurring wildfires and disasters causing fires. The source of fire in particular is quite useful to know, as sources of fire can be subject to compositional differences from other sources which may result in other kinds of nutrient resources as well as unique carbon pooling.

Otherwise, this report is subject to some limitations in its investigation that ought to be addressed relative to the research proposal. Namely, future research should aim to outline the locale either natural or laboratory facilitated that analyses are conducted on due to geographical variation. Additionally, the type of plant as well as the state of growth thereof the plant. Each of these variables opens up new avenues for research on the topic of microbial burn response and by all means, ought to be considered for future studies.

References

Adkins, J, Docherty, KM, Gutknecht, JLM & Miesel, JR 2020, ‘How do soil microbial communities respond to fire in the intermediate term? Investigating direct and indirect effects associated with fire occurrence and burn severity’, Science of The Total Environment, vol. 745, p. 140957.

Adkins, J, Docherty, KM & Miesel, JR 2022, ‘Copiotrophic Bacterial Traits Increase With Burn Severity One Year After a Wildfire’, Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, vol. 5.

CLARKE, KR 1993, ‘Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure’, Austral Ecology, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 117–143.

Dove, NC, Klingeman, DM, Carrell, AA, Cregger, MA & Schadt, CW 2021, ‘Fire alters plant microbiome assembly patterns: integrating the plant and soil microbial response to disturbance’, New Phytologist, vol. 230, no. 6, pp. 2433–2446.

Hebel, CL, Smith, JE & Cromack, K 2009, ‘Invasive plant species and soil microbial response to wildfire burn severity in the Cascade Range of Oregon’, Applied Soil Ecology, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 150–159.

Singh, D, Sharma, P, Kumar, U, Daverey, A & Arunachalam, K 2021, ‘Effect of forest fire on soil microbial biomass and enzymatic activity in oak and pine forests of Uttarakhand Himalaya, India’, Ecological Processes, vol. 10, no. 1.

Whitman, T, Whitman, E, Woolet, J, Flannigan, MD, Thompson, DK & Parisien, M-A 2019, ‘Soil bacterial and fungal response to wildfires in the Canadian boreal forest across a burn severity gradient’, Soil Biology and Biochemistry, vol. 138, p. 107571.

Criminology

This openbook exam was written for the University of Otago in the paper GEND209 with an expected word count 1900 plus or minus 10% (1912 total). References were not requested for this assignment, and all content draws from learned content of the course. There is also an additional section of two questions each approximately 300 words each.

The victim is a continuously turbulent subject in criminal justice and media-socio-cultural debate whose existence is judged by the moral trends shared and passed on through historical accounts of public righteousness. One of the leading influences on defining virtue, morality, and pragmatism comes from the commonplace religious followers whose teachings continue to hold judicial and social capital. Christianity in Western society while significantly less omnipresent in the present day, has branded itself into the common philosophy of what is just, insofar as shaping the reactions, processes, and relationships that surround criminal offending and victimhood. In more ways than one, Jan Van Dijk in their work “Free the Victim” written in 2009 critiques the intimate relationships of victims and Christianity through the exploration of victim experience, the experience of social spectators, and the scriptures that etymologically and epistemologically define what and how it is to be a victim.

When we assess what is meant by the Christian values that surround social response to victimhood, we must ask to epistemological and etymological meanings of victim in the contexts of Christian societies. Western countries such as the US have a rich history immersed in Christian belief systems, the word victim itself from the religious angle represents something of a powerful sacrifice. In the Christian faith, Jesus Christ was made victim to a Jewish tribunal death by crucifixion after he proclaimed status as the king of the Jews, as part of a mockery and punishment. Through his sacrifice, Jesus is recognised as a saviour to mankind, and his sacrifice of blood is done out of selflessness for humanity’s redemption. Sacrifices religiously too aren’t done without purpose, as offerings to supernatural forces are done to bring about goodness in times of tension and turmoil. When Van Dijk evokes the word victim, this idea is largely what they refer to. According to Van Dijk, the victim was first used in English to describe the of experience Jesus Christ which thereby ascribes a deeper religious interpretation to how victimhood is interpretable. To be a victim therefore is a high proclamation, and the sacrifice of victimhood is morally ought to be a position of altruism as Jesus Christ did.

Jesus is described as a passive victim in his crucifixion, whose passion and forgiveness of his killers surpass any amount of resentment for them. The central theme is dying for the ones you love. The ideal victim in the image of Christian virtue is expected to “carry their suffering gracefully and offer their attackers unconditional forgiveness.” (Van Dijk 2008, page 20). Also, in contrast, Van Dijk states that “Such forgiveness serves the interests of both community and offender but not necessarily the interests of the victims themselves.” (Van Dijk 2008, page 20). Valuable, if we grant Christian values being foundationally relevant to victimhood as Van Dijk suggests, the public perception perceives victimization as a status to upholster honour in the name of stilling social turmoil. Perplexingly then, victims are unmined in the victimization process by being presumed a responsibility variable enough to be a deeply conflicting undertaking. Rather the victim's support for their ordeal is hampered as compassion for their experience isn’t unconditional as their forgiveness is.

In the modern day, victims employ their voices in writing to convey experiences, but the capacity to tell an experience doesn’t confer persuasiveness to the reader. Narratives are often patternable with themes of resentment, and anger denouncing the offender, overcoming adversity for a survivor is paramount to internalizing their strength. Even more notable is the selflessness of victims to support others through activism. Van Dijk points toward protagonists of victim narratives such as Natascha Kampush, who provides rich accounts of the dynamics of deviant and strong victims, who neatly fit many of the patterns of victimhood and resilience. However, such victimhood patterns are contradictory to the ordinary and expected to be perceived victimhood narrative, as the judgement of society has to clash with the articulation of the victim in conjunction with media and bias. Individuals subjugated to such social judgements can thus become delegitimized victims whose story may not be told readily, well enough, or conformly enough to be properly appreciated, and hence victims especially non-ideal victims whose social position isn’t in line with common Christian idealism, are rendered invisible. Even on the political scale, Christian values especially patriarchal values result in differential treatment of victims such as those of marital rape. Marital rape continues to be a polarizing cultural phenomenon because while rape itself is handled with severity, marital rape is handled more recklessly. Ideologically the difference in rape severity is stringent on the religious belief of women’s position as subservient to the man in marriage, which to Van Dijk’s credit reduces the agency of women furthermore and only continues to shape invisible and idealism in victims by the public. This is also true in relationships of marginalization such as non-Christian sanctioned LGBT relations that in some religious texts and communities are demonized and undermined.

Connecting the imagery of Jesus Christ’s crucifixion through Van Dijk’s interpretation along with victims today; victims are given a choice to be a passive victim or have the media experience good enough to articulate themselves in an environment that is actively hostile to victims. Symbolically as Christ forgave his killers, Van Dijk suggests the victim must be as he, lest they become sacrificed to scapegoat for the problems perceived by the wider society. In the religious hodgepodge, you need to be a victim in the way society wants to see a victim, and by acting beyond the expectations of a victim, a victim opens themselves up to suspicion, hatred, and criticism.

Where all these concepts culminate is the idea of the “ideal victim”. Ideal victims as a concept are individuals afflicted by an offence and identifiable or portrayable in such a way as to evoke emotional responses, empathy, and relatability. Such identifiers admit them a state of perceivable undeserving suffering, often laying foundations for outrage and fear for safety at the indirect behest of the offending party. Core to the societal reaction is the invigoration orchestrated by media in conjunction with common social and cultural morality and values. Conveniently many social and cultural values, to the credit of Christianity’s religious influence, tend to coincide with one another concerning the tarnishing of a victim from an ill offender. Victims who are not ideal due to a lack of conformance to what makes an ideal victim are excluded from the social reaction relevant to ideal victims via exclusion and invisibility.

The ideal victim often tends to carry the characteristics of an innocent do-gooder whose circumstances, relationships, and history do not contradict a puritanical perception of engendered roles and expectations. For instance, women who could perceivably be part of one’s victimization through precipitating the crime would not be ideal. But a woman of strong family orientation, modestly dressed, fair, white, woman, faithful, and with a promising future among other features are assertedly ideal for an ideal victim image. It is the victim image based on the severity of the victimhood that garners exposure, either voluntarily or involuntarily, Large-scale scale cases are sensationalistic because their exposure is great, and draws attention. Part of the reason why ideal victimhood is used isn’t to summon compassion for the ideal victim, but rather to “demonize the offender as a totally evil person” (Van Dijk 2008, page. 15).

Culturally speaking, Christianity is grounded very deeply in puritanism and social altruism. In the context of a victim, Christianity asks for a victim to “love not just our kind but also our enemies and to practice forgiveness” (Van Dijk 2009, page. 22). Through this expectation of forgiveness, the impact against an offender from a victim is softened, but the onus remains on the victim to forgive on behalf of the offender. The inability to forgive, which in extreme victim cases isn’t unexpected, draws the ire of Christian values as the principle of love thy enemies is forgone and the passivity most specially associated with women is discarded. The ire of Christian values can then open a victim up to scapegoating and shift of blame unto the victim, often referring to the victim as an accomplice and instigating factor as a form of secondary victimization. Part of the reason for this as Van Dijk points out, is that non-conformance to ideal victimhood requires a performance, but a performance is largely up to the scrutiny of interpretation of the consumers of the content. For instance, Van Dijk refers to the case of Madeline McCann, whose secondarily victimized parents due to television appearances didn’t passably appear as victims which led to doubts about their authenticity. Van Dijk explains this is because of doubts about their parental competency which evolved into claims of their hand in the case as perpetrators turning them into scapegoats for the offense which was only worsened by the media leaning into the scapegoat narrative. Victims in this framework are as a result more inclined towards silence and passivity in the guise of Van Dijk’s ideal victim Christian narrative as the more outspoken a victim is, the more they incriminate themselves for secondary victimization.

Van Dijk links the ideal victim directly to the Christian ethos of the meaning of the word victim directly in how society reacts to discontent victims. To shove ideal victimhood leads directly into secondary victimization in the form of victim blaming and scapegoating as by “blaming the victim for their fate, we reassure ourselves we live in a just world” (Van Dijk 2009, page. 13). It is then, as a religious ritual to sacrifice something for the greater good, the victim is sacrificed involuntarily for not adhering to their engendered role. The social reaction, in turn, discards the victim’s agency and conditionally refers to them as a victim. In regards to Natasha Kampush, Van Dijk also demonstrates the unrest surrounding how a victim is treated alters the validity of the victim. Natasha was a victim celebrity whose experience enraptured the victimhood arena until reports were discovered some of the treatment she received in the late stages of her kidnapping. Van Dijk purports Natasha was painted to be a participant in her kidnapping after an influx of compassion suddenly stopped by reports of going with her kidnapper to a skiing resort. Or consider the victimized family of Madeline McCann, whose lack of passivity only led them to be secondarily victimized to justify and cull unrest.

Jan Van Dijk’s Free the Victim, I believe makes a compelling case for the prevalence of Christian values having an “unspoken but powerful” impact on the experiences of victims and social responses to victims. The media, social, and cultural perceptions of what makes a compelling victim are all entwined in a perception of passivity that parallels the altruistic vision of Christ’s death. To be outspoken as a victim is to be provocative against the common emotional response and experience of hearts and minds that merely read of the victim and offender. Van Dijk is literal in that it is impactful in an unspoken and powerful way, for victims are not to speak for their own sake. That provocation as Van Dijk attests and reinforces, is an affront to the values of what makes an ideal victim, ideal to the commons, and it is used poetically in the religious sense to promote “real” victims and sacrifice fallible victims in reactive victim scapegoating to make up for the problems asserted not by the victim but made into the victim by the populace.

Mini Bibliography

Van Dijk, J 2008, ‘In the shadow of Christ ? On the use of the word “victim” for those affected by crime’, Criminal Justice Ethics, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 13–24.

― 2009, ‘Free the Victim: A Critique of the Western Conception of Victimhood’, International Review of Victimology, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 1–33.

Section B1

Question: Provide an argument in favour of, and an argument against, replacing the term ‘victim’ with ‘survivor’.

The term survivor is entirely built on securing the image and individualism of the offended party. To be a victim is to have been irrevocably damaged and to hold the status of victim also pertains to an inability to overcome that of which victimized them. There also exist cultural symbolisms and meanings that edit how the word victim is perceived, to what extent and in which way is one victimized? By an offender, a system, or circumstance, the word victim tends to betray the complexity by which circumstance and perspective exist. The term survivor instead of victim ameliorates the negative cultural connotations that come with the word victim, and it instead ascribes the ability for the offended party to move on from their afflicting event and heal actively.

In contrast, to be a victim infers legally to be someone whose been legitimately affected in some way. The word victim informs that someone hasn’t healed and that there is a need for support, understanding, and progression to move on. It also holds the offending party to the blame as a survivor is beyond the event as the word victim resonates in media sensationalisation with the public as it evokes certain cultural meanings and ideals where survivor does not. Such meaning and ideals can be detrimental to the victim in question, but it draw attention and action quickly to a situation of importance which as a tool in activism, is arguably useful. Although the victim excels where the survivor doesn’t, survivors are given the responsibility of moving on if incorrectly labelled.

The terminology of victim and survivor is ultimately a matter of the choice, and circumstance of victims/survivors, both having strengths in language for different reasons and therefore are equally delicate and feasible for use in victimological contexts.

Section B2

Question: How and by whom was the term ‘victim blame’ first defined, and what is the value of this concept in victimology?

The term victim-blaming came from William Ryan, whose use of the term referred to the use of hostility and fixation on the defects of a victim to justify and soften the blows of legitimate inequality whose inequality begat victimhood. Explanations and mechanisms of victim blaming are conceptualized in early victimological theoretical accounts by Hans von Hentig and Benjamin Mendelsohn whose victimological theory included the victim in criminal acts.

Victims were considered possible active participants of a criminal act, for a victim should be present for an offender to exist, and a motive should be present for an offence. One of the theories to explain this phenomenon was called “victim precipitation” which suggested that the victim played a key part in which a crime is precipitated thereby handing over some responsibility for the crime to the victim by provoking a crime. Hence the victim is responsible for “blame” for what had made them a victim, hence “victim blaming”. Reactive victim scapegoating is also done, in which a victim is reacted to by the social and cultural observers of their plight, at the victim’s expense usually by discrediting them, sometimes by blaming them in part.

Socially this shift from looking at the crime committed to the victim who precipitates is very important in victimology, for concurrent social attitudes to a woman who walks the night alone of various circumstances such as wear, whereabouts, and social connections is placed upon a spectrum of blame should something criminal occur to them. It’s a reverse lens by which to look at criminal offending introducing the victim into the thoroughfare as a more prominent variable of offending called “positivist victimology”.

This essay was written for the University of Otago in the paper GEND209 with an expected word count 2500 plus or minus 10% (2455 total). A total of 13 references were used.

The political sphere as a constant in society continues to evolve to the ever-changing and turbulent public opinion and political landscape. The marketplace of ideas as it were, ought to be understood between more than just one regiment of belief, much as there exist multiple forms of feminism for instance, there are also multiple forms of practising those feminisms. Victimology concerning victim politics voices a divide between what is meant by a victim rights movement as opposed to victim activism.

In Western society, there ought to exist a system of law and morality as decided by the state as answered to the democratic masses, although the meaning of law and morality as cultural issues become complex dilutes. In a case that is dubbed “the Stanford Sexual Assault case” as overviewed by Nickie Phillips and Nicholas Chagnon (2018, pp. 48-49, 54-56), victimology can find a fascinating mobilization of victim politics in forms of carceral feminism and penal populism. The Stanford case follows a sexual assault and rape of an unconscious victim by a perpetrator called Brock Turner, whose assault was intercepted by two Samaritans who described a disturbed recount of the victim’s circumstances. What riled people up, is the court settled on a light sentencing of six months in prison. Both these victim political entities of penal populism and carceral feminism are deeply rooted across the political victimological theory in which the public cultural perspective contains allusions to the preference for state-authoritative sentencing. Part of the reason for these entities’ omnipresence is due to the perception of rampant rape culture. The outrage became a political spectacle, whose adjacency to the criminal justice system made for an effective political strategy for politicians to secure votes for “tough on crime” promises of policy. What followed was a bloodthirsty approach to cultural victim politics, that went on to cleave society on matters of victims and offenders in ways that would go on to fail to solve problems they assertedly began to cause.

The Political Arena of Carceral Feminism and Penal Populism

Victims of sexual abuse, rape, and other sex-adjacent crimes are subject to a great amount of attention that finds itself atomizing between eliminating the offences and supporting the survivors of these atrocities. Carceral feminism is a major contender in this field and is referred to as according to Terwiel (2019, pp. 424-427) a movement that wants to integrate higher amounts of policing and prosecutorial systems and harsher punishments as a means of solving sexual and gender violence. The beliefs of carceral feminism have friction with other feminist movements such as those of prison abolitionist perspectives, especially given that carceral values are documented to have incidentally reinforced intersectional injustices to marginalized communities despite carceral feminist goals. Although neither side of the fence on the carceral topic is necessarily correct, and conversationally has been diluted into a base binary that is in reality a lot more complex.

Clare McGlynn (2022, pp.3-4) affirms that the carceral feminist model and its critics such as anti-carceral feminists and prison abolitionist feminists tend to rely too closely on binaries of justice, and the goals of a reformative movement for victims and institutions are too ambitious and multi-faceted. To lean too far into a carceral motive or non-carceral motive opts for consequences on either side at the potential expense of security or the victim. So, what McGlynn and Terwiel thereby purport, is that both motives can be coterminous with foundational multi-leveled consideration and transformation of both public opinion, the carceral state, and the government among other institutions. To complement that kind of transformation is a call and push for what they refer to as “continuum thinking” which promotes critical thinking approaches to step to the complexity of criminalization, the justice system, and those including minority communities who interact or ought to interact with them.

Although politically, perspectives on crime are less pragmatic; Penal Populism refers to the phenomena in which politicians to secure public interest for their electoral benefit take advantage of public concerns over alleged levels of crime by taking a policy stance that is tough on crime advocating for reinforcement of the criminal justice system, and harsher punishment systems for offenders. Public opinion is atomized as demonstrated by a psychological study by Côté-Lussier (2016, pp. 235-236, 243-244). Looking into the populace of the UK, US, and Canada, trends correlated with a desire for harsher punishments in combination with specific factors that are emotionally driven by anger, disgust, and inconsiderate of preceding factors. Even while these attitudes in favour of harsher punishment, are frivolous complementary to trends of sentencing and offending. These perspectives of harsher punishment from Côté-Lussier’s study also link the punitive attitude toward what they refer to as a “racial animus’ in which inequality between intersectionality such as race informs severities of the penal perspective. Albeit this study contains critical limitations to its research, it provides an opening to a model to describe attitudes of criminals albeit from a compromising construction model that perceives otherness as a factor for offending.

These factors for a political stance, neatly parallel with reporting surrounding victimology such as the works of Lepore (2018) as perspectives begin to undertake more institutional approaches without recognizing the compromission of victims. In turn, penal populism has turned victimization and offending around victims as an effective propagandistic tool subject to the vulnerability of security which fuels negative perspectives on how to solve problems on victim rights. It is then victim rights movements that come to represent each side of the political debate on victims’ rights through movements like #MeToo, and thus coalesce a legitimate debate on effective justice.

On Victim Activism: Reformation and Critical Analysis

Victim activism often takes the form of an institutional or communal entity in society, that works to provide agency to a group of people. As an activist movement, victim activism seeks to seek out mechanisms and systems that drive victimization narrative and perceptions, on a foundational level. Such activism thereby requires a deep critical analysis of underpinning social, cultural, and judicial systems to incite large-scale change. Nicole O’Leary and Simon Green (2020, pp. 160-162, 165-167) recognize there exists a failure of justice that provokes a palatable pattern in victim activism campaigns. O’Leary and Green describe the dissolution of crime management in conjunction with victims, adjacent to the complex institutional structure of political manipulation and social-cultural commentary that pushes political agenda. An example of such an agenda is observable in the research by Elizabeth Whalley (2020, pp. 213- 214)

who highlights concurrent systems that solve problems of victimization such as crisis centres, when integrated with legal-institutional forces like police, are counter-intuitive to the process of supporting victims. Concerning the #MeToo movement in Sweden, victim activists referred to their movement as an advocation for “pragmatic justice” rather than the oppositional appeals to “carceral justice”. From the perspectives of Lena Karlsson (2024, pp. 3-7) they voice those feminist perspectives of justice have delineated the pointers of success in victim justice, referring to a quote by McGylnn and Westmarland “Justice is a lived ongoing and ever-evolving experience and process, rather than an ending or result”. What came about from #MeToo was thereby a moment in activist history to inform of the lived experiences and allow people to speak out to communicate as a form of the justice process. This was especially important to activists in what is referred to as “the justice gap”. As Loney-Howes, Longbottom & Fileborn (2024, pp. 3-6) describe, the activist movement pushes towards centres against sexual violence, and sheltered and support services for the disenfranchised with the philosophy of helping victims over punishing criminals. The “justice gap” continues the pattern of justice not being a goal of incarceration, but rather a variable ongoing process of multiple unique factors. Although traditional perspectives on justice remain in the mainstream, victim activism, through gradual change can refocus feminist and state resources into victim support over the interrogative carceral system.

Critiques of the criminal justice system's competency with victims are only reinforced by the works of Lara Bazelon and Aya Gruber (2020). One of the matters broached in the context of #MeToo is victims whose needs transcend that of otherwise unfulfilling carceral and policing systems. One popular solution is restorative programs that promote instead healing victims and prevention of continued offences. Part of the reason Bazelon and Gruber purport this alternative support is that the service is providing the victims more support rather than disposably using the victims as a tool for the carceral system. Turning a victim into a proverbial tool has wrought more damage than help to victims as it tends to victimize marginalized groups, prioritize, and approach confounding factors under-managed by the carceral system in unsatisfactory ways.

Bazelon alongside Bruce Green (2019, pp. 7-12, 18-22) analyzed the feminist divide in depth, at the start of the developments of victims' rights, the movement focused on finer outcomes for women across different circumstances such as marital rape. However, the aim was distorted into what is called an “improvement of the criminal adjudicative process” under the presumption that punishment of offenders is optimal remediation for a wronged individual. The victim activist side of matters opted to instead reform the way that core systems interact with victims which believed punishment was only a deterrent, and arguably not the greatest deterrent. The greatest deterrent was for victims in the carceral system who would have to trudge through their victimization and marginalization from media narrative to ideology and institutionalized focuses.

Thereby and assertedly the problem is a very politically fractured multi-level structure of foundational socio-cultural and political intersections in victimization, justice, and offending which victim activism seeks to resolve, because what we already have and more thereof doesn’t solve the origin of many victimological problems.

Victim Rights Movements: Complacency and Layman Cultural Morality

Victim rights movements in contrast to victim activism are in simple terms, significantly less actively involved with the victims, and their victimization events and more concerned with victim rights and entitlements within the criminal justice system. Definitionally, it is victim rights movements that voice public opinion to incite change and shape public action on the legislative level to ascribe rights to victims. Holder, Kirchengast & Cassell (2020, pp. 3-4) suggest human rights as perceivably absent and are a progenitor of injustice whilst absent. There within victim injustice, victim rights movements seek to remedy it either by using already preestablished mechanisms to further include victims, and victim rights into the institutional contract of legal parties. Hence giving the right to know about one’s rights, summon those rights, and have entitled to those rights leads to justice for a victim. The challenge, however, of victim rights movements, ultimately comes down to the moral philosophy argumentation and efficacy of integrating victim rights effectively into systems.

Some victim rights movements such as that of the #MeToo movement are divisive. #MeToo became a social media phenomenon of victims, which were mostly women concerning generally sexual and partner violence, who would tell their stories of their negative experiences. Laurie Kohn (2019, pp. 563-569) describes the turbulence of the movement, from its anonymity of allegations to the extreme effort onlookers took to take the allegations seriously or even challenge allegations and their victims, especially in the case of high-profile celebrities. Although efforts were largely unsuccessful in any matters outside of giving a voice to victims and raising awareness by sparking debate, the problem was without a clear prescription for justice and veritable communication.